We are created by what has happened to us, combined with who we choose to be.

Rating: 5/5

Trigger warning: Domestic violence, animal cruelty, abandonment, child abuse

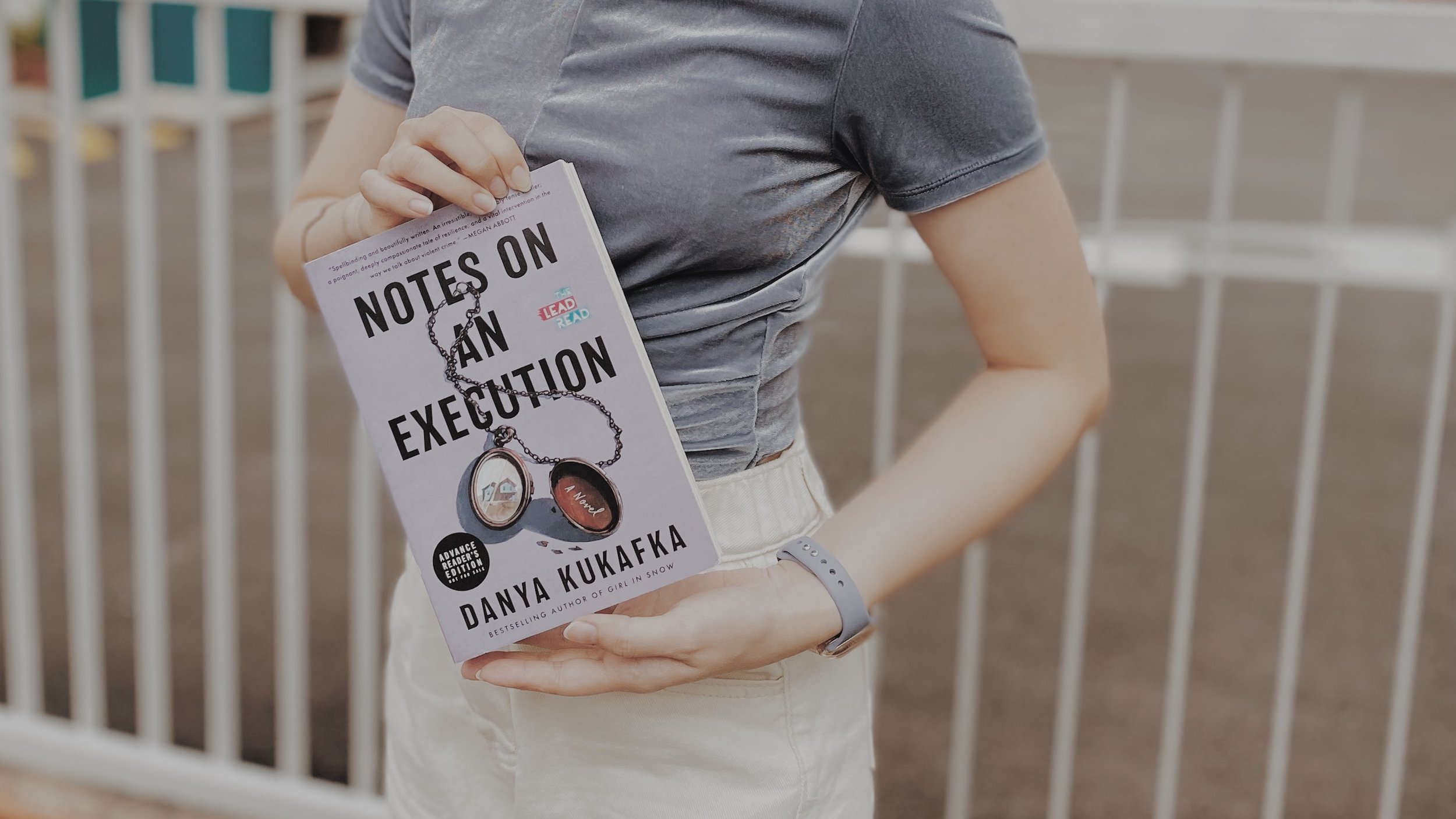

This book left me with so many things that I never really considered on a daily basis. First off, just let me say this—I absolutely loved and enjoyed this book. So very much. The fact that its pub date coincides with my birthday is definitely an icing on the cake!

Again, I won’t provide any synopsis because you can easily google that for yourself, and I won’t be value-adding anything to the synopsis. And I do have a lot to say, so let’s organise things a little as we jump in. Starting off with the pace of the book—it was just right, with us having Ansel’s point of view, which is the countdown to his execution day, and the alternating chapters from the various women who were somewhat related to him or affected by what he’s done. I do find that Saffy’s later chapters move a little slow, though, with that constant dance between showing herself and trying to not to get involved. In fact, I feel like for all the women that were involved, she’s the least likeable—while I understand how a single incident in her childhood could cause her trauma, which may follow her through to adulthood, I found her relentless self-pity suffocating. She was so stuck in the past, yet she couldn’t make up her mind when she was finally in the position to do so. It took her so long to eventually do what she did that I felt like those chapters were a little draggy. That being said—her parts are still enjoyable to read and it could be just my personality that’s speaking—I can’t stand people who can’t make up their minds—though in her case I suppose I should still be patient with her even though she’s just a fictitious character suffering from a form of PSTD.

Where is the line, between stillness and motion?

And then the plot twist! My goodness, the twist. I was finishing up my lunch in office when it came, and I had to sit still for a few minutes to contemplate what I had just read (and my own existence). It was so shocking when it came! It was when I had to remind myself that Ansel is a convict, so his version of the events that happened would obviously be quite unreliable. I mean the events still happened to him personally and it’s his truth, but at the end of the day, I had to remember that the actual truth is made up of different versions of how the events unfolded. One person’s truth can and will never be the absolute truth. This also begs the question—if two people remember the same event in a different way, whose recount should be taken as the truth? This is why I always believe in photographic or recorded evidences—but even then, each of our interpretation of an event unfolding within the photograph could differ. What happens then? When it comes to crime and judgement, everything is just so grey.

While this book is about how men are always being glorified by the media when they commit a crime, and how it changes the narratives of a woman’s life, one of the main takeaways I had was how the justice system will always be flawed, because humans are essentially flawed beings. Who are we to decide who’s absolutely right and who’s absolutely wrong? And how do we judge the time period of a person’s jail sentence? Finally, how do we assess if a convict has a high rehabilitative possibility?

If a person has committed a crime as serious as murder, does that mean that we, as a society, have the right to subject him to the death penalty? Or are we taking away his right as a human to live, and to possibly rehabilitate? It’s a very grey area. Are we acting based on collective good when we sentence a convict to the death penalty because we think that there will be one less bad apple on Earth, even if that means we’re infringing on another human’s right? Or do we consider it not as a collective good, but as collective selfishness instead—an entire society bent on having someone dead for killing someone else, for their own benefit? And in this case, because the benefit affects the majority, does this mean that it is the right thing to do? Who are we to decide that we should end someone else’s life because they’ve done something morally unsound?

Very few people believed that they were bad, and this was the scariest part. Human nature could be so hideous, but it persisted in this ugliness by insisting it was good.

On the other hand, one could argue that the convict did have a choice. Everyone has made choices to get to where we are at right now. Every single action we make is a choice. When someone says ‘I have no choice’, is it essentially to excuse themselves from their responsibility of making the choice, and to absolve any mistake that may arise from that choice? And could we also then say that it is selfishness on the convict’s part to even make the choice that lead them to this outcome? Isn’t it also selfish of the convict to place themselves in this situation and force society to judge them?

Then we have jailing—is it right for law-abiding taxpayers to be providing for jailed convicts? These citizens have worked hard for their money, too, and it is of course necessary to pay their taxes so the state has the finances to take care of them in one way or another. But in cases when we jail someone, the convict now has free meals three times a day. We pay to keep the jails in as humane a condition as possible. We pay to feed these convicts who have made bad decisions and are thus kept behind bars to keep society safe again. In this way, law-abiding citizens are now providing for the ‘bad apples’, who should instead be out there contributing to the general good of the society—do you see the irony I’m getting at?

I could go on, except that I’m typing this really late at night and I think I should stop now. I hope I’m still coherent so far. This will be a long discourse, and it’s also something no one would have a right answer for. There’s no right or wrong when it comes to the belief that you subscribe to in terms of the justice system, which makes it an extremely difficult and sticky topic to discuss. But nonetheless, definitely think about this a little bit—these are some thoughts that came up when I finally finished the book.

Going back to the book—I do wish there was some sort of closure in terms of why Ansel’s version of what happened during his childhood is so different from what actually transpired. Though I’d say that would be a nice to have, since it doesn’t really affect the story all that much. All in all, an absolutely stunning book. Brilliant writing, beautiful prose, and top it off with Kukafka’s tactful approach to the topic, I strongly recommend for you to pick this one up.